Overview through the prism of Montessori theory by Vincent Bardot

Resume

The role of music in human development is a topic that is receiving increasing attention from various scholars. However, the role of music remains poorly understood, especially in the development of children and adolescents. The constructive contributions of music (in listening, in practice, in writing) as well as its dangers for development are generally little considered from an educational perspective. This paper will review the literature on the subject by examining the contributions of the various sciences in the light of Maria Montessori’s theory. It aims to understand the role of music on the development of adolescents on different levels (physical, physiological, emotional, social, spiritual) and to identify ways to implement musical support for optimal development of adolescents in a prepared environment.

1 Introduction

“There is no complete spiritual life without music, for the human soul has regions which can be illuminated only by music.”

Zoltán Kodály

Maria Montessori described development from birth to adulthood. There are developmental phases, called » plan of development « . The period of adolescence is one of them and extends from 12 to 18 years according to Maria Montessori.

Each “plan of development” intended to allow the human being to develop certain faculties. Each plan has its own characteristics and needs. In broad terms Maria Montessori defines adolescence as a social age where the human being develops more deeply his personality.

It is in this light that we propose to study the role of music in adolescence. Indeed, the observation will make us note that

Music is an integral part of adolescence. Whether it is listened to, sung, played, alone or with others, whether it provokes dancing or retreating to a bedroom bed… music sets the pace.[2]

- What needs are met by listening to, playing or composing music at this age?

- To what extent does music provide development help?

- Can it become an obstacle?

- How helping better the adolescents’ development thanks to music?

2 Music and human development : A Montessorian overview

Before looking at the role of music in adolescent development, it is interesting to define our purpose: what is music? What role does music play in human development in general? How do you explain adolescents’ deep interest in music in this light?

2.1 What is music? a human need and a language

Music is an art. That is, a human capacity to create a « psychosphere »[3]. The Encyclopedia Britannica gives this definition:

Music, art concerned with combining vocal or instrumental sounds for beauty of form or emotional expression, usually according to cultural standards of rhythm, melody, and, in most Western music, harmony.[4]

Music can be described as the most « social » art insofar as it can be practised collectively and embellishes all the events of social life: “music has many different functions in human life, nearly all of which are essentially social”[5] noted Dr. Hargreaves in The Social Psychology of Music. It has been described since ancient times as a factor of social cohesion and a religious force, “bringing human beings in pitch with cosmic harmonies”[6].

Indeed, some theories[7] explain that music would have had the function of allowing our species to synchronise its behaviour, to access a superior form of group life and to contribute to the emergence of more organised societies. An explanation of music as an emotional regulator is sometimes given, music would participate in a channelling of wild forces[8]. It is worth noting that the ancient myths have transcribed this idea in the form of Orpheus taming animals with his lyre.

As for religions and philosophers, there are innumerable explanations, more or less similar. Pythagoras or the Vedic religion make music a gift given by the Gods to connect with the divine worlds and understand the universe[9], a religious force (religere, “bound” in latin, the humans between them and to the gods). Music allows the expression of beauty in time, unlike architecture which does so in space. Music is also linked to physical expression through dance.

Maria Montessori’s eyes, music is seen as a “spiritual need” of the “supranatura”, especially in the subgroup « culture and arts », « religion » and « vanity ». What will interest us particularly is that music is also part of the need for « vanity », that is to say in the need of the human being to assert an identity excluding others. The musical taste for example is the expression of it.

Music in self-expression and psychic culture

Maria Montessori includes it in the « self-expression » part of her syllabus for the adolescent as one the “ways of expression”[10]. However, she gives it a more prominent place for the child. Music could also be part of the “psychic culture”[11] as a language. During the Middle Ages music was part of the educational quadrivium. It was brought closer to the other arts (astronomy, arithmetic, geometry) [12], connected to arithmetic.

In various places in her work, Maria Montessori links music to language, calling for the education of children to become familiar with the language of music, both in listening and in writing. She advocated an intelligent and non-mechanical listening to music as a language that contains meaning:

To make the hearing of music an intelligent act and not like the mechanical process, which appears when children read, in loud monotone, books which they cannot understand and of the meaning of which they have no idea.[13]

Musicologist, Deryck Cooke devoted a book to the subject showing that music is constructed as a real language and that linguistic vocabulary can be used to describe music, The Language of Music[14] .

Maria Montessori paid a great deal of attention to this, bringing listening to music closer to listening to language in the child’s psychic formation in the chapter “How language calls to the child” of Absorbent Mind:

The ear does not respond to every sound in the universe, because has not enough strings, but those it has can resonate to complex music, and a whole language can be transmitted in all its delicacy and refinement.[15]

Furthermore, she explained that, for the child, language is at first a kind of music that gradually takes on meaning: “the music coming from a person’s mouth has a purpose”[16]. Music would therefore in reality be the first language of the human being with three components: melody, rhythm and harmony.

In our approach, we can distinguish the modalities of adolescents’ relationship to music: simple listening to mechanical music, deep listening, practice, composition. We will also look at the links between music and poetry and of course dance.

2.2 Music in the light of human development

Before birth

Music and sound participate in the construction of the subject’s identity from the very first moments of his life, in the prenatal intra-uterine world.[17]

It is indeed remarkable that it is through the sense of hearing that human beings come into contact with the outside world. The impact of prenatal music listening is not well known but appears to be significant.

Childhood

The child explores music primarily as a medium for sensory learning. There is evidence that listening (or making) to music contributes to the formation of the human auditory system and brain. Before the evidence of neuroscience, Maria Montessori had noted this in Absorbent Mind. She also devotes an interesting chapter to the issue in The Montessori Method called “musical education”[18] as part of “the education of the senses”[19].

Various studies show the constructive role of musical practice for the auditory system, language areas and motor development. To mention just two studies, we can first mention the study of Andrea Norton and Marie Forgeard, « The effects of musical training on structural brain development: a longitudinal study » (2009). This study showed that making music impact and improve the structure of the brain in children, particularly in areas associated with auditory perception, sound processing and fine motor skills. We can also mention another study[20] which reports the positive influence of early music exposure on language acquisition.

However, in adolescence and adulthood, the role of music is more confused. Different functions can be distinguished.

2.3 Music in the light of adolescence’ sensitive periods: why do adolescents listen to music ?

The evidences of a sensitive period ?

Having approached the role of music in the development of the child, we will better understand what happens in adolescence, because there’s a shift. It should be noted with the Dolf Zillmann and Su-lin Gan in a chapter of The Social Psychology of Music about “Musical taste in adolescence”, « the enormity of adolescents’ consumption of, and apparent fascination with, various forms of music. »[21]

It would be wrong to think that this is a recent phenomenon linked to the possibility of listening to music almost everywhere with Ipods, Smartphones :

The relationship between music and teenagers is extraordinary. At no other time in life does music hold such a central role as it does during adolescence. The average teenager living in the developed world spends approximately two-and-half hours per day listening to music – a figure that is hard to believe for most adults, but was common average across many studies, even before iPods came into existence and made music listening more accessible (Brooks, 1989 ; Brown and Hendee 1989). [22]

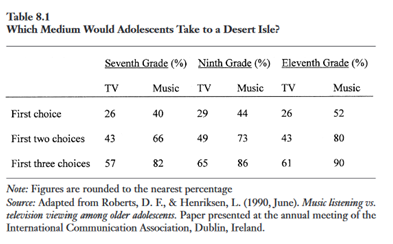

A paper from Roberts, D. F. and Henriksen, L. (1990), shows that music is the preferred form of entertainment for adolescents and that this trend increases during the adolescence. [23]

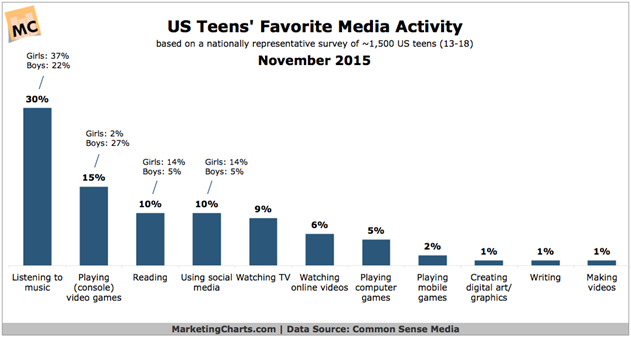

It was still the case in 2015 in the USA, according to Common Sense Media[24] :

What happens then? What is the need for this sudden huge consumption of music? Why can we speak of a « sensitive period » for music in adolescence?

Psychological characteristics of the adolescents explaining the need of music

The concept of the sensitive period defined by Maria Montessori explains that the human being is sensitive to certain realities of his environment according to the needs of his development plan. The sensitive period for music in adolescence is quite distinct from the sensitive period for music in children, which is part of the “sensory sensitive period”. This sensitive period could be a sub-sensitive period of the “personal dignity” which is a main sensitive period for adolescents.

Indeed, the adolescent is interested in music for other reasons than the materiality of sound and the exploration of sounds. Adolescents listen to music on their own initiative and develop a very intimate connection to what they listen to. To understand why, let’s use a concise encyclopaedic definition of the adolescent period:

Adolescence: Period of life from puberty to adulthood (roughly ages 12–20) characterized by marked physiological changes, development of sexual feelings, efforts toward the construction of identity, and a progression from concrete to abstract thought. Adolescence is sometimes viewed as a transitional state, during which youths begin to separate themselves from their parents but still lack a clearly defined role in society. It is generally regarded as an emotionally intense and often stressful period.[25]

This definition, like that of Maria Montessori, emphasises the transitory dimension of this period of transformation. The adolescent goes through a period of fragility and at the same time of affirmation where music plays an important role.

According to this definition and the various books I have read on the subject, it is worthwhile to consider the role playing by music for the adolescents from different prisms:

- the physical and physiological development

- the emotional development

- the personality and identity development

- the social development

- the spiritual development

From this set of psychological characteristics, links to music are quite evident without any judgment on it:

| Psychological characteristics of the adolescent | Link to music |

| Biological level | |

| Physical changes | dance to tame a new body |

| Physiological changes | rhythms helping homeostasis |

| Discovery of sexuality | dance and partners expression of beauty analogy to natural seduction parade[26] sexual lyrics |

| Emotional and psychological level | |

| Construction of the personality | exploring tastes finding, asserting tastes find a model in the artists or in an aesthetic |

| Emotional intensity and troubles | means of expression mood management, emotional response to music |

| Love feelings and relationships | romantical lyrics social facilitator |

| Intellectual and spiritual level | |

| Need for abstraction | abstract language of music |

| Need for meaning | approaching philosophy, meaningful lyrics, through the songs |

| Spiritual development[27] | art as self-transcendence, mysticism of music, contemplation and meditation aesthetic experiences |

| Social level | |

| Separate from parents | join a band find a social family represented by the musical group or the fans |

| Finding a role in the society | sharing tastes and a culture with peers make music with others create music for others |

In other more Montessorian terms, adolescents seek to meet certain needs through listening to or playing music. The human tendencies of “exploration”, “communication”, “repetition” and “self-perfection” are particularly visible.

3 From a developmental support to an obstacle

We propose to review the various aids that music seems to bring to the adolescent’s development, before considering that a certain relationship to music can become an obstacle to development.

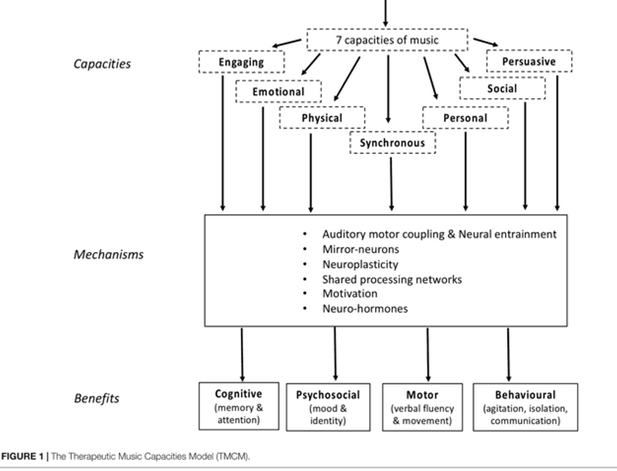

This diagram[28] reviews the different capacities of music, its mechanisms and its benefits. This grid can be used to analyse the contributions of music when it comes to adolescents’ “creative and cultural development benefits, quality of life benefits, social dans emotional development benefits”[29].

3.1 The rhythmic role of music in responding to the transformation of the adolescent : factor of homeostasis

The first function that would explain the powerful attraction of adolescents for music would be explained by a physiological parameter.

An article from a psychological journal, “From the individual to the group: the place and function of rhythm in the reorganisation of identity in adolescence” (translated by me from French), makes an interesting connection between the musical rhythm sought by adolescents and the rhythmic upheaval of puberty transformations:

During adolescence, the subject is confronted with new sensory experiences that will modify his relationship to his psyche and therefore his relationship to the world. The music and the sound will come to register in this change. […] In this sound and musical experience, rhythm holds a very privileged place. The rhythm is at the very base of the constitution of the body-self and of the feeling of continuity of existence […] Moreover, one observes a direct link between the biological, internal, body rhythms and the musical rhythms. As for adolescence, it is this moment where the rhythms are disturbed by puberty: do we not speak about the changes of the food or sleep rhythms?[30]

This connection between the rhythmic component of music and the rhythmic upheaval in the human being as an adolescent must attract our attention. Indeed, one could explain the fact that the adolescents seek in the music by their need to find a rhythm building for their new organism, psyche, identity.

Music would then potentially intervene as an aid to development if it provides rhythms capable of providing a support, an anchor for the adolescent’s development.

It is clear that a certain type of music is favourable to helping rhythmic organisation of the human being, especially adolescents, as proven by this 2010 study “Society Effects of classical music listening on rhythm perception and cardiovascular” which correlates improved cardiac functions and relaxation with listening to quiet classical music:

The greatest benefit on health is visible with classical music and meditation music, whereas heavy metal music or techno are not only ineffective but possibly dangerous and can lead to stress and/or life-threatening arrhythmia.[32]

Music could therefore play an important role, especially in practice, in helping adolescents through this period of rhythmic upheaval.

3.2 Potential role of music in the accompaniment of emotions regulation, exploring feelings

Regulation of emotions

It is worth recalling how Maria Montessori defined the period of adolescence as a “time of crisis”:

This is a time of crisis during which all the glands of internal secretion are affected, and, through them, the whole organism. The body is growing rapidly but not at a uniform rate, and this results in a disturbance of functional equilibrium.[33]

Adolescents’ interest in music, particularly when listening to it on a quasi-bulimic basis, would stem from the need to soothe emotions and a sensitivity that is on the verge of bursting:

First, one of the more important functions of popular music for adolescents is what we have called the “primacy of affect” (Christenson & Roberts, 1998). Teens (and most age groups) frequently use music as a tool to maintain or change particular moods, and they readily admit that music has direct, profound effects on their emotions.[34]

This function of music is well known since antiquity, as witnessed by Aristotle in the 4th century BC who describes the three functions of music in The Poetics:

As for music, its action is above all effective on the soul and the passions, it possesses a cathartic function, an ethical function and an aesthetic function, the first because it is capable of purging certain emotions by expressing them, the second because it is capable of making the listeners more moderate and virtuous, the third because it offers a source of aesthetic pleasure to the listeners.[35]

The “cathartic function” of music as a pharmakon would therefore have a major role in accompanying the development of the adolescent. A study has proven this assertion:

Music affects the cardiovascular system through multiple potential mechanisms including the autonomic nervous system and the vagus nerve which responds to musical vibrations by triggering the body to relax. Music also affects other parts of the brain, which in turn affects the mood through the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine. Dopamine release may contribute to the study findings which found that 83% of subjects found fast music uplifting. Finally, nearly all subjects believe music can help manage stress. Listening to music may be a potential therapeutic method for reducing anxiety and depression.[36]

It is obvious that musical practice will offer greater effects than just listening. Scientific evidence has been provided to support these statements, as a 2022 study:

Results indicate that most studies report significant effects for mental health outcomes related to social and emotional improvements and reductions of internalizing symptoms for adolescents […][37]

Exploring, shaping, sharing feelings

During adolescence, the human being gains access to a new sensibility which he explores in particular through the aesthetic experience of music:

During adolescence, the subject is confronted with new sensory experiences that will modify his relationship to his psyche and therefore his relationship to the world. Music and sound are part of this change.[38]

It should also be noted that the use of a language beyond words, a language of emotional expression (as we have defined it) such as that of music, allows adolescents to express a part of themselves unfiltered and gives them the feeling of being understood in an empathetic way through musical listening or composing:

Music has been shown to accurately communicate basic emotions and previous studies have identified particular musical features (e.g., tempo, sound level, timbre) that relate to the expression of discrete emotions such as happiness, sadness, anger, fear, and tenderness in music (Gabrielsson and Lindström [2001]). [39]

Music can therefore become a medium for positive sensory, emotional development and enable human beings to reach a higher form of empathic humanity.

The adolescent urge for universal communication beyond spoken language finds its paroxysm in the desire of certain young musical creators:

Often young music makers have the feeling that they will appropriate or invent a language for themselves.[40]

Turning off the mind

The use of music also helps adolescents to put their psychic activity on hold, to “muffle of the psychic apparatus”[41]. This underlines the “adaptive function” of music in dealing with a period of life that can be delicate because of its intensity.

3.3 Potential role of music in the accompaniment of the construction of the identity and its social role

This statement by Maria Montessori seems to place the practice of art as a fundamental activity for the adolescent:

The chief symptom of adolescence is a state of expectation, a tendency towards creative work and a need for the strengthening of self-confidence[42]

Creative work should be an important part of the adolescent’s life. More than that, Maria Montessori describes the adolescent as a period of « inner revelations”:

Then comes the epoch of adolescence, an epoch of inner revelations and of social sensibilities.[43]

Developing personal tastes, find one’s style

Therefore, listening, making, liking music, with the affirmation of tastes, anchors them in the culture, they find their materials, reference points for the construction of their identity:

Music and sound participate in the history of the subject, in its individual construction and in the relationship, it has with its environment, whatever its culture.[44]

Adolescents develop their own tastes through listening or making music, and these tastes will structure their entire lives. It participates to the « efforts to find one’s own style»[45] which can be approached as a human tendency.

Dave Miranda, Ph.D from the University of Ottawa, in a fascinating article on the subject “The role of music in adolescent development: much more than the same old song” [46], explains that the faculty of “aesthetic appreciation for music” is rooted in adolescence:

In fact, adolescence seems to be a critical period for developing musical tastes as they may develop into familiar cognitive prototypes through acculturation. In fact, a 21-month longitudinal study confirmed that aesthetic appreciation for music is developed in early adolescence and that it stabilises during late adolescence.

The role of music in adolescence is therefore foundational, since it then conditions a whole part of human existence in adulthood. Adolescents build a “personal playlist” that becomes the soundtrack of their lives: “music is their soundtrack during this intense developmental period.”[47] Hence the extremely sensitive and intimate link between adolescents and the music they like, and the way in which the music listened to in adolescence becomes what is known in psychology as a “foundational experience” of adult identity[48].

Music’s badge function[49]

Music also allows adolescents to join a social community marked by a style and sometimes values, especially in high school where “it is usually easy to classify many subgroups of adolescents according to their music preferences”[50]:

They use music as a ‘badge’ that shapes their peer groups and peer crowds, which are often known as ‘musical subcultures’. These musical subcultures develop a youth culture identity and provide informational and normative social influences[51]

Many adolescents find in music making a way to join a new family as “Social Newborns”[52], to be recognised by a community and find their role in the society:

In sum, developmental psychology should take notice that music is not only a ‘social lubricant’ in adolescence (as it can be in adulthood). Music is a resource from which adolescents decide to explore possible selves, rehearse social roles, manage intergroup dynamics, and envisage future orientations (e.g. artistic careers) by observing their peers and favourite musicians.[53]

Listening and participating in music is a need for their social independence:

Conceptually, the impetus for seeking and joining a taste culture is usually linked to adolescent maturation ; specifically, to the transition from parental protection and guidance to self-determination and independence.[54]

Support for social and love experiences

For many adolescents, dance was or still is a way of exploring sensuality and provides an opportunity to discover the other. However, Esteban Buch notes that « recorded music has been very important in the rituals of seduction throughout the twentieth century, » allowing « individuals to choose for themselves music that is appropriate to the temporality of their encounter”[55]. Historically, music has influenced adolescent love experiences and continues to do so, generally by generating problematic behaviour nowadays[56].

Nevertheless, music, especially love songs and dance, just as poetry did and sometimes still does, would help adolescents to enter the world of seduction and love by giving them “cultural guidelines” from the world of adults. Music also provides a cultural framework for adolescent’s relationship development, especially when adolescents share the same tastes. Musical artistic expression can provide a medium for their emerging sensuality.

3.4 Potential role of music in the spiritual development of adolescents: personal world view, religious feelings, aesthetic experiences, contemplation and meditation

Definition of spiritual development

There remains one aspect of human development that is too often forgotten: it is what we might call the “spiritual development” of the human being. In 2003, psychologist Peter L. Benson have given an experimental definition of it:

Spiritual development is the process of growing the intrinsic human capacity for self-transcendence, in which the self is embedded in something greater than the self, including the sacred. It is the developmental “engine” that propels the search for connectedness, meaning, purpose, and contribution. It is shaped both within and outside of religious traditions, beliefs, and practices.[57]

Within “spiritual development”, adolescence would be a pivotal period:

Issues of meaning, purpose, vocation, relationships, and identity are particularly salient during adolescence.[58]

A 2013 Finnish study indicates that music plays a major role in adolescents’ construction of “personal world view” and religious feeling:

According to the data, music offered tools for constructing personal world view and was experienced to strengthen confidence on higher power or life itself. As a mental resource, music had an important role in coping with life.[59]

The role of music for adolescents would then have a much deeper function: it would help the human being to nourish religious, mystic feeling, and could play an epiphanic role in transforming their vision of themselves and the world.

The discovery of aesthetic experience, the spiritual epiphany

A largely underestimated role of music in the adolescent’s development is that of a revealing agent enabling adolescents to access the aesthetic dimension of life in the form of “epiphanies”[60]. This mysterious region of the human’ sensitivity is difficult to define, even by the cognitive sciences which give it a special status between emotion and judgement. It is one of those “inner revelations” described by Maria Montessori.

Art is more than just visible or sound stimuli. It corresponds to a lived experience (vivencia). It produces a kind of resonance in us: it is the aesthetic experience that puts us in communion with the universe and ourselves.[61]

Music here does not simply play the role of « taste shaper »[62] or the “psychosocial constructor” we identified before, music plays here the metamorphic function of transforming a whole relationship to the world and to oneself as in a quasi-religious conversion. While for the child there is a kind of latency period in personal artistic expression, there is an explosion of activity in the fields of art :

For precocious artists, the end of adolescence is a creative moment that is sometimes essential (musicians and poets), for example.[63]

Various hypotheses have been put forward to explain this phenomenon; it would be related to the « awakening of sexuality”, the development of « human love » creates a sublimated form in « the love of art »[64] in particular.

Contemplation and meditation

The need of adolescents to listen to music alone and regularly could also be likened to a form of contemplation reminiscent of religious contemplation and meditation: attention fixed on an aesthetic object, evoking another world, allows the soul to connect with something greater than the immediate experience circumscribed by the finitude of human life. In this respect, René Voillaume described “The need for contemplation”[65] as an essential need of human being. For a long time, this particularity of the adolescent has been identified notably by the philosopher Gaston Bachelard in La Poétique de la rêverie[66].

3.5 Potential role of music as an obstacle to development: overview of cultural and technological threats leading to disorientation

To what extent can music become an obstacle to adolescent development?

Critical period for the identity and social behaviours: disorientation

Music is not just a collection of “melodies, rhythms and harmonies” as we defined it at the beginning. Music can convey through its aesthetics, its style, the lyrics for the songs, a whole way of life. In fact, it is by these criteria, especially “lifestyle”, that “subcultures” [67] identified by their musical affiliation are sociologically defined.

As adolescence is a fragile period, it is obvious that this fragility can lead adolescents to be manipulated or exposed to degrading content:

Adolescence is a critical period for the gradual development of identity (Côté, 2009). Social media can provide opportunities for adolescents to explore potential selves and develop identity (Roberts et al., 2009). Kistler, Rodgers, Power, Austin, and Hill (2010) showed that music is a source of social cognitive norms that impacts the development of adolescents’ self-concept.[68]

Since the 2000s, adolescents’ exposure to potentially degrading content through the Internet has increased significantly, especially through social networks where music plays an important role

Adolescents structure themselves on the basis of social norms that they observe: what if these norms are destructive? What if the artists they identify with incite degrading behaviour?

Indeed, research has shown that the behaviours conveyed in certain musical lyrics or music videos have a profound influence on the behaviour of adolescents:

Additionally, music often reflects and reinforces the themes and values that are important to adolescents, including sexuality. Research has shown that music can have a profound impact on sexual behaviour and attitudes, both positively and negatively, depending on the content and context of the music.[69]

As educators of adolescents, therefore, we need to consider the exposure of adolescents to musical influences « in all directions » as influences that emanate from an unprepared environment and that can potentially, and not systematically, hinder the development of a troublesome personality and lead to problematic behaviour.

Subculture groups: risky behaviours and drugs

At the extreme, but quite frequently, listening to certain types of music can actually lead the adolescents to drug-taking:

The potential influence of music on adolescents’ risky behaviours (e.g. substance use, risky sexuality, self-harm) is also receiving a lot of attention. Popular songs can convey great amounts of messages about drugs; and adolescents’ exposure to such lyrics is associated to their actual substance use (Primack, Douglas, & Kraemer, 2009). The influence of musical subcultures on adolescents’ substance use also seems to be partially mediated by their socialisation with substance using peers (Mulder, ter Bogt, Raaijmakers, Gabhainn, Monshouwer, & Vollebergh, 2009).[70]

This music-related issue should not be neglected when it comes to supporting the development of adolescents. Since studies show that music can lead adolescents to behaviours that are toxic to their physical and mental health. Indeed, since music causes an alteration in the state of consciousness which can to some extent be compared to drugs according neurosciences[71] (Robert J Dr Zattore), there is sometimes a very fine line with taking real drugs.

This is particularly the case in certain musical subgenres where drug use is part of the aesthetic and creative process like “psychelic music”, a “subculture of people who used psychedelic drugs such as 5-MeO-DMT, DMT, LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and mescaline, to experience synaesthesia and altered states of consciousness.”[72]A study has “demonstrate[d] how themes in drug-related songs parallel the stages of addiction”[73]. We could also mention the “rave culture”[74] for example, in which drug-taking is a cultural element.

This penchant of music to influence the moral dimension of the human being undoubtedly tells us that music has also to do with moral education, as it was understood in Antiquity[75], the “formative education which will construct firm foundations for the character”[76], as it leads to or threatens the “spiritual equilibrium”[77].

This propensity of adolescents to expose themselves to different dangers can be explained by their desire to find a cultural family, by identification with the cultural subgroup and willingness to participate in the group’s common culture, by peers’ influence. Coupled with family fragility, there might be a high risk:

There is substantial evidence that adolescents who are depressed, angry, alienated, experiencing suicidal thoughts, having family problems, abusing drugs

or alcohol, or having difficulty at school constitute a group that is particularly

drawn to the sort of angry, nihilistic music that celebrates these “troubled”

states and traits. These factors, when coupled with the high levels of identification with the music and its performers, seem at the very least cause for

reason to be concerned […][78]

Music isolation through technology

“There are many mental afflictions that occur during adolescence”[79] noted Maria Montessori. Adolescents might develop a disease, “a sense of melancholy”, the “hebephrenia”, then they “can be driven to suicide”[80]. The impact of music on this matter has been studied.

In a study called, “Adolescent suicide: music preference as an indicator of vulnerability.” Dr Christoper G. Martin investigated possible relationships between adolescents’ music preference and aspects of their psychological health and lifestyle:

Significant associations appear to exist between a preference for rock/metal and suicidal thoughts, acts of deliberate self-harm, « depression, » « delinquency, » drug taking, and family dysfunction. This was all particularly true for girls.[81]

Repeated and prolonged listening to certain music enabled by technological loops could then lead to the known psychological phenomenon of “amplification”:

Moreover, some of the research on music’s impact on mood suggests what might be called an “amplification effect,” a strong tendency for music to heighten whatever emotional state a listener brings to a listening situation—including anger and depression (Gordon et al., 1992; Wells, 1990).[82]

Listening to music in isolation, alone in one’s room, is a phenomenon to be investigated. This solitary activity may satisfy a need for intimacy specific to adolescent development, but in excess it also leads to asocial behaviour which, surprisingly, denies the profound reality of music as a social activity.

The issue of sterile wandering, reverie, isolation: disembodied music

As Maria Montessori noted, the human mind must grasp its faculties through creation, otherwise it risks becoming engulfed in an indigent dreaming passivity:

Imagination was not given man for the simple pleasure of fantasizing […] Imagination does not become great until man, given the courage and strength, uses it to create. If this does not occur, the imagination addresses itself only to a spirit wandering in emptiness.[83]

Daydreaming, “reverie” is an important characteristic of the adolescent, some of which are necessary, including « poetic reverie », « project reverie » and « regret reverie »[84]. However, those necessary moments of solitude should not become the main activity of adolescents. This would be dangerous for their social development.

An aggravating factor in the adolescent’s dreamy propensity can be identified. Dr M. Twenge, PhD, professor of psychology at San Diego State University wrote a very interesting book on the subject with the suggestive title : iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood.[85] She writes in the opening remarks, among other things:

The complete dominance of the smartphone among teens has had ripple effects accros every area of IGeners’ lives, from their social interactions to their mental health.[86]

Then, it is clear that music plays a role in the complete dependence that some adolescents have on their smartphones: in listening to music per se, but also in videos, films, series, because music is everywhere. The music then “functions as a drug”[87], the siren song of Odysseus, potentially keeping the adolescents under hypnosis. Music then becomes an obstacle to social development and incarnation, keeping them in a semi-conscious state.

Dr. M. Twenge also reports that:

the number of teens who spend time with friends on a daily basis dropped by 40 percent between 2000 and 2015. Recent studies describe Gen Z as the loneliest generation claiming that members of that cohort report more feelings of isolation and loneliness than any other demographic group.[88]

We can for example mention the trend of « airbuds » connecting to smartphone making adolescents in certain environments listen to music non-stop altering the quality of their presence in the world and with others.

The state of isolation and statism then leads to psychic fantasies that are often destructive, in any case far removed from the realities of preparation for adult life. It leads, according to Dr. J M.Twenge to a “narcissism epidemic”[89].

Physiological disorder

Finally, studies have shown that listening to certain violent music can disturb the homeostasis:

heavy metal music or techno are […] possibly dangerous and can lead to stress and/or life-threatening arrhythmia.”[90]

Although studies dedicated to adolescence do not really exist on the subject, one can imagine that the effects of such music disturb the different systems in transformation of the adolescent.

4 Exploring ways to support adolescent development with music

Adolescents listen to, make and write music in an unprepared environment. What about the prepared environment for music? In the light of this literature review, some suggestions for helping adolescents to develop through music can be extracted.

I believe that one of the first steps is to consider musical expression as being within the reach of every human being and not reserved for some, as Maria Montessori pointed out :

We tend to think that the realm of music is the privileged area of some happy few. Experience has taught us, however, that if offered the right kind of education from a very early age onwards, anyone is capable of entering the realm of music.[91]

Listening music as an “intelligent act”

If music is an expressive language, it can be learned, taught or self-taught. Listening and practising together will help adolescents to access the language of music. The quality of presence in listening will then increase as this language becomes familiar. There are some scientific evidences showing that in the field of music “the adolescent brain remains receptive to training, underscoring the importance of enrichment during teenage years.”[92]

Promoting the involvement of the body in making music and the group practice

We have seen the dangers of listening in too much isolation (not to be confused with the intimate musical meditation of adolescents, which is a deep, almost religious need) and the risk of de-socialising adolescents and losing them in “psychic reverie”. As an art of the invisible, music can be a force of disembodiment or incarnation.

Involving the body -the presence of the body- in the music is an interesting lever: collective dance, group practice, are all tracks that will increase the positive development of adolescents and participate in a more successful and balanced construction of the personality.

- Positive physical and physiological effects can be expected:

The links between music and motor skills are also well documented in non-musical subjects. In 1888, Nietzsche said “We listen to music with our muscles. Indeed, certain musical excerpts are said to promote body tone and spontaneous improvement of posture (Forti, Filipponi, Di Berardino, Barozzi, & Cesarani, 2010[93]

2. Emotionally and socially benefits can also be expected when the body is involved:

Several studies have highlighted the positive effects of group music-making and have suggested that it may be the creative and social aspects of such activities, which have a positive effect on participants’ wellbeing.[94]

Music becomes then a “facilitator-group dynamics”[95] for the adolescents’ interaction.

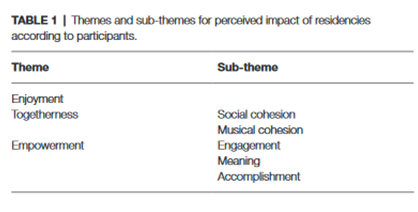

This chart, taken from the book The Impact of Music on Human Development and Well-Being[96], synthesises “key words” that describe a residential experience that was carried out around collective music practice: “social cohesion”, “engagement”, “accomplishment”. These words describe emotional states of great interest to adolescents. Music then fulfils a cognitive, social and cultural function. Music contributes here to the “value of the personality”[97], to the extent that it creates “positive experiences” [98] with social recognition.

Offering a variety of possibilities for experimentation in style and aesthetic experiences

We remember the fundamental place given by Maria Montessori to « self-expression » in accompanying the development of the adolescent’s personality. She calls for the implementation of “[…] ways of expression, which through exercises and external aids will help the difficult development of the personality.”[99]

It is clear that an environment that offers the adolescent opportunities for rich musical expression by exploring on their own different musical genres and styles is necessary.

Cultural enrichment is important here and also contributes to “the preparation for adult life”. The adolescent should be able to discover and explore musical styles that transcend his time, the anecdotal of the “social norms” [100] which can be alienating. Given the richness of the repertoire of music created by mankind, there is much to offer the adolescent to build a culture and a sensitivity that will contribute to a deeper adult life.

Thought should also be given to which musical genres are most likely to help adolescents calm their bodies (studies have shown the beneficial effects of classical music).

To finish, I would like to talk about an interesting book (Michael Johnson, Making Music in Montessori, Everything Teachers Need to Harness Their Inner Musician and Bring Music to Life in Their Classrooms, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2020), more suitable for children, but which will open up avenues for the development of a prepared musical environment for adolescents.

5 Conclusion

To briefly summarise the answer to the question « what is the role of music in adolescent development? « , we would say that music plays a multidimensional role.

Music meets different needs of adolescence as a “social age”:

- Need to find a building rhythm in a rhythmically troubled period

- Need to soothe emotions in a solitary way

- Need to express and share emotions beyond words or with music lyrics

- Need to explore tastes, find their tastes and affirm it

- Need to develop sensuality and love experiences: music provides a medium for dancing, expressing feelings of love

- Need to share a culture, tastes and live in a community outside the family circle symbolised by the musical subgroup, to find their style

- Need to explore the “aesthetic experience” as a dimension of human’s life which enriches it and makes it more profound

- Need for spiritual development: music contributes to the construction of a vision of the world, of a relationship with life and with others, to commune with something beyond themselves

As we have noted, music is fundamentally social -don’t we talk about social harmony- so it is not surprising that adolescents take to it with such passion.

Overall, music has an adaptive function and helps adolescents through a period of profound transformation by providing a multi-functional pharmakon support: it helps with homeostasis, “mood management” and emotional exploration, expression.

Music is also a force for social cohesion in that it allows adolescents to find their peers and acts as a real « social facilitator ».

In particular, the exceptional role of music in structuring identity, personal taste and spirituality should be highlighted. Music is a vector of aesthetic experience, often the source of the founding experiences of the identity of the future adult.

However, music also poses great dangers, commensurate with its potential benefits. Music, especially through new technologies, can keep adolescents isolated, in fruitless reverie and lost in narcissism.

Music can also convey an invitation to unhealthy and destructive behaviour (drugs, delinquency, suicidal behaviour, sexual issues etc.), and many studies show correlations. Didn’t Plato wrote in Περὶ πολιτείας[101] that it is through the distortion of music that social chaos first arrives?

Finally, I think it would be interesting to look at musical education in antiquity, where it played a major role, especially in moral education.

Vincent Bardot, 12-18 AMI Educator

6 Bibliography and some books commented

You will find all the sources I have used at the foot of the page, each time I quote a passage. I read a lot on this topic and used a variety of sources (books, articles, studies). I would like to present here three works that caught my attention.

- David J.Hargreaves, The Social Psychology of Music, Oxford University Press, 1997.

This book is totally fascinating on the subject. It draws on social and developmental psychology and ethnomusicology to examine the way in which music contributes to the social construction of personality and groups.

The chapters « musical tastes in the society » and « musical tastes in the adolescence » are really worth reading for those who like the subject. I found concepts and structuring information.

The last chapters question the practices around music, particularly from the point of view of therapy, consumption behaviour and musical education.

Those who teach music will also find an interesting chapter “the social psychology of music education.

- Dave Miranda, “The role of music in adolescent development: much more than the same old song”, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 2013.

Dave Miranda is a doctor of psychology from the University of Ottawa and a specialist in the influence of music on young people. His work is outstanding.

This brilliant article provides a synthetic but very structured overview of the issue. I like the precision of the chapters and the data I used to answer the question I asked myself. It seems to me to be a “must” on the subject.

There is much food for thought here that would deserve entire books to be developed on the subject of adolescents and music.

His other work on the subject can be found on the university’s page: https://uniweb.uottawa.ca/members/851/profile

- Jean M. Twenge, iGen: why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy – and completely unprepared for adulthood, Atria books, 2017.

- Jean M. Twenge, W. Keith Campbell, Atria Books, Narcissism Epidemic : Living in the Age of Entitlement, Atria books, 2010.

Jean Marie Twenge is a professor at the University of San Diego and a prolific researcher in the field of generational psychology. Her work on the new generation and the damage of new technologies can be a source for dialogue with educators and parents of students.

These two books are more distant from our subject on the surface, but for me they are deeply connected. Indeed, music is nowadays completely linked to technology: this situation provokes a mutation of behaviours that we have to consider especially in the new generations. There is a lot of material to be extracted from these two books about how technology impacts on the development of adolescents.

These books are no-nonsense and try to lucidly confront a reality that in many ways is frightening.

In particular, I would like to study in the light of her two books the way in which the needs of adolescents and the human tendencies described by Maria Montessori are diverted by many technological uses.

[1] René MAGRITTE, Chapeau melon, Musique et Colombe

[2] Vincent Cornalba, L’Adolescent et sa musique, In Press, 2019. (Translated from French)

[3] By ”psychosphere”, Maria Montessori designated the cultural and psychic world created by the human being as opposed to animals living only in a biosphere. See Maria Montessori, The Absorbent Mind, Chapter 8, ”The Child’s conquest of Independance”, AMI, p. 82.

[4] Epperson, Gordon. « music ». Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/art/music, march 2023

[5] David J.Hargreaves, The Social Psychology of Music, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.1.

[6] Yukiko Tsubonou, Ai-Girl Tan, Mayumi Oie, Creativity in Music Education, Springer Nature Singapore, 2018, p.170.

[7] Yukiko Tsubonou, Ai-Girl Tan, Mayumi Oie, Creativity in Music Education, Springer Nature Singapore, 2018, p.12.

[8] Patrik N. Juslin and John A. Sloboda, Handbook of Music and Emotion: Theory, Research, Applications, 2010.

[9]Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier, Pythagoras and His Influence on Thought and Art in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, 2007, p.84.

[10] Maria Montessori, From Childhood to adolescent, Appendix B, AMI, p.71.

[11] Idem.

[12] Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier, op.cit, p.63.

[13] Maria Montessori, The Montessori Approach to Music, AMI, p. 73

[14] Deryck Cooke, The Language of Music, OUP, 1959.

[15] Maria Montessori, The Absorbent Mind, AMI, p.110.

[16] Idem., p.110.

[17] Anthony Brault, Marie Rose Moro, « De l’individuel au groupe : place et fonction du rythme dans les réaménagements identitaires à l’adolescence » inLa psychiatrie de l’enfant, 2018/1 (Vol. 61), p.135-148

[18] Maria Montessori, The Montessori Method, Schocken, 1988.

[19] Maria Montessori, The Montessori Method, Schocken, 1988.

[20] “Musical intervention enhances infants’ neural processing of temporal structure in music and speech » de Christina Zhao et al. Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2017. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1603984113

[21] David J.Hargreaves, The Social Psychology of Music, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.161.

[22] Katrina McFerran, Adolescents, Music and Music Therapy, Methods and Techniques for Clinicians, Educators and Students, « What is healthy adolescence and how does music help ?, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2010, p.60.

[23] Media Violence and Children, A Complete Guide for Parents and Professionals, Chapter 8, « The Effects of Violent Music on Children and Adolescents », Praeger, 2003

[24] https://www.marketingcharts.com/industries/media-and-entertainment-60878

[25] Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. « adolescence summary ». Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/summary/adolescence.

[26] Darwin’s theories is also relevant to our topic, in The Descent of Man, Darwin explains that music made by humans is a continuation of natural music, as in the courtship of birds, and would be related to reproduction and would have been a factor in natural selection : »Musical tones and rhythm were employed by the semihuman ancestors of man during the mating season » in BUCH Esteban, Musique et sexualité, Editions MF, 2022, p.262.

[27] The concept of “spiritual development” will be deepen infra.

[28] Evangelos Himonides, Gary E. McPherson, Graham F. Welch, Jennifer MacRitchie, Michele Biasutti, “Beliefs and values about Music in Early Childhood Education and Care : Perspectives From Practionioners”, The Impact of Music on Human Development and Well-Being, Frontiers Media SA, 2020, p.25.

[29] Idem.

[30] Anthony Brault, Marie Rose Moro, « De l’individuel au groupe : place et fonction du rythme dans les réaménagements identitaires à l’adolescence » inLa psychiatrie de l’enfant, 2018/1 (Vol. 61), p.135-148

[32]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/47729215_The_effects_of_music_on_the_cardiovascular_system_and_cardiovascular_health

[33] Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence, AMI, p. 70.

[34] Douglas A. Gentile, Media Violence and Children, A Complete Guide for Parents and Professionals, Chapter 8, « The Effects of Violent Music on Children and Adolescents »,Praeger, 2003, p.165.

[35] Aristote, La Poétique, Les Belles Lettres, 2014, p.47.

[36] Darki C, Riley J, Dadabhoy DP, Darki A, Garetto J. The Effect of Classical Music on Heart Rate, Blood Pressure, and Mood. Cureus. 2022 Jul 27.

[37] Rodwin, A.H., Shimizu, R., Travis, R. et al. A Systematic Review of Music-Based Interventions to Improve Treatment Engagement and Mental Health Outcomes for Adolescents and Young Adults. Child Adolesc Soc Work J (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-022-00893-x

[38] Anthony Brault, Marie Rose Moro, « De l’individuel au groupe : place et fonction du rythme dans les réaménagements identitaires à l’adolescence » inLa psychiatrie de l’enfant, 2018/1 (Vol. 61), p.135-148.

[39] Saarikallio, S., Vuoskoski, J. & Luck, G. Adolescents’ expression and perception of emotion in music reflects their broader abilities of emotional communication. Psych Well-Being 4, 21 (2014).

[40] DOUVILLE Olivier, « De la musique dans l’espace psychique des adolescents », La lettre de l’enfance et de l’adolescence, 2007/3 (n° 69), p. 97-103. (translated from French)

[41] Lecourt, É. (2006). Le sonore et la figurabilité. Paris : L’Harmattan, coll. « Psychanalyse et civilisations », p.97.

[42] Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence, AMI, p. 60.

[43] Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence, AMI, p. 88.

[44] Anthony Brault, Marie Rose Moro, « De l’individuel au groupe : place et fonction du rythme dans les réaménagements identitaires à l’adolescence » inLa psychiatrie de l’enfant, 2018/1 (Vol. 61), p.135-148

[45] Hellmuh Benesch, Atlas de la psychologie, La Pochothèque, « Psychologie de l’adolescent », p.293.

[46] Dave Miranda (2013) The role of music in adolescent development: much more than the same old song, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 18:1, 5-22, DOI:10.1080/02673843.2011.650182

[47] Dave Miranda (2013) The role of music in adolescent development: much more than the same old song, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 18:1, 5-22, DOI:10.1080/02673843.2011.650182

[48] We will develop infra the role of the “aesthetic experiences”.

[49] David J.Hargreaves, The Developmental Psychology of Music, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.171.

[50] Douglas A. Gentile, Media Violence and Children, p.158.

[51] Dave Miranda (2013) The role of music in adolescent development: much more than the same old song, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 18:1, 5-22, DOI:10.1080/02673843.2011.650182

[52] Maria Montessori used this expression.

[53] Idem.

[54] David J.Hargreaves, The Developmental Psychology of Music, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.172.

[55] Estan Buch, Musique et sexualité, Editions MF, 2022, p.125. (Translated in French by me)

[56] See infra 3.5

[57] Benson, P. L., Roehlkepartain, E. C., & Rude, S. P. (2003). Spiritual development in childhood and adolescence: Toward a field of inquiry. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 205–213

[58] Idem.

[59] Murtonen, Sari. “The role of music in young adults’ spiritual development.” International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 23 (2018): 209 – 223.

[60] Jean-Marie Schaeffer, L’expérience esthétique, Gallimard, 2015.

[61] Debesse Maurice. L’éducation esthétique. In: Bulletin de psychologie, tome 16 n°218, 1963. pp. 716. (Translated from French)

[62] Idem., p.721.

[63] Idem. , p.714

[64] Idem., p.714.

[65] René Voillaume, The Need For Contemplation, Darton, 1972.

[66] Gaston BACHELARD. La poétique de la rêverie. P.U.F., Paris 1960 in Debesse Maurice, « L’éducation esthétique », Bulletin de psychologie, tome 16 n°218, 1963. pp. 715.

[67] David J.Hargreaves, The Developmental Psychology of Music, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.148.

[68] Dave Miranda, The role of music in adolescent development: much more than the same old song, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 2013, 18:1, 5-22, DOI: 10.1080/02673843.2011.650182

[69] “Much More Than the Same Old Song » by Laurel J. Trainor, published in the journal Developmental Psychobiology in 2014, page 633.

[70] Idem.

[71] Salimpoor, V., Benovoy, M., Larcher, K. et al. Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nat Neurosci 14, 257–262 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2726

[72] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychedelic_music, The link between music and drugs is such a social phenomenon that it has an extensive page on Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_use_in_music), and cannot be ignored when it comes to adolescence.

[73] Mark A. Adolescents discuss themselves and drugs through music. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1986;3(4):243-9. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(86)90035-8. PMID: 3586073.

[74] Philip R. Kavanaugh and Tammy L. Anderson. 2008. “Solidarity and Drug Use in The Electronic Dance Music Scene.” The Sociological Quarterly 49(1): 181-208.

[75] See infra Plato, The Republic.

[76] Maria Montessori, « The Reform of Secondary Education”, Communication 2011/1-2, p.84.

[77] Maria Montessori, « The Reform of Secondary Education”, Communication 2011/1-2, p.84.

[78] Douglas A. Gentile, Media Violence and Children, A Complete Guide for Parents and Professionals, Chapter 8, « The Effects of Violent Music on Children and Adolescents »,Praeger, 2003, p.165.

[79] Maria Montessori, « The Adolescent – A “Social Newborn », Communications 2011/1-2, p.77

[80] Maria Montessori, « The Adolescent – A “Social Newborn », Communications 2011/1-2, p.77

[81] Martin G, Clarke M, Pearce C. Adolescent suicide: music preference as an indicator of vulnerability. 1993 May;32(3):530-5. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00007. PMID: 8496116.

[82] Douglas A. Gentile, Media Violence and Children, A Complete Guide for Parents and Professionals, Chapter 8, « The Effects of Violent Music on Children and Adolescents »,Praeger, 2003, p.165.

[83] Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence, AMI, p.19.

[84] Debesse Maurice, « L’éducation esthétique », Bulletin de psychologie, tome 16 n°218, 1963. pp. 715.

[85] . M. Twenge, iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood. New York, NY: Atria. ISBN: 978-1-5011-5201-6 paperback. 342 pp.

[86] Idem

[87]« Édith Lecourt (2006) entrevoit la musique à l’adolescence comme pouvant jouer un rôle de « nourriture » qui peut, dans certains cas, prendre l’allure d’une drogue. (p. 97) » in De l’individuel au groupe : place et fonction du rythme dans les réaménagements identitaires à l’adolescence Anthony Brault, Marie Rose Moro DansLa psychiatrie de l’enfant 2018/1 (Vol. 61), pages 135 à 148

[88] https://psmag.com/ideas/have-headphones-made-gen-z-more-insular

[89] Jean M. Twenge, W. Keith Campbel, The Narcissism Epidemic, Atria Books, 2010.

[90]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/47729215_The_effects_of_music_on_the_cardiovascular_system_and_cardiovascular_health

[91] Maria Montessori, The Montessori approach to music, p.11.

[92] Adam Tierney, PhD, and Jennifer Krizman of the Auditory Neuroscience Laboratory and the School of Communication. “Music Education Alters Adolescent Brain Development” https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1505114112

[93] La musique comme outil de stimulation cognitive, Aline Moussard, Françoise Rochette, Emmanuel Bigand Dans L’Année psychologique 2012/3 (Vol. 112), pages 499 à 542 (translated from French)

[94] Evangelos Himonides, Gary E. McPherson, Graham F. Welch, Jennifer MacRitchie, Michele Biasutti, “Exploring Welbeing and Creativity Trough Collaborative Composition”, The Impact of Music on Human Development and Well-Being, Frontiers Media SA, 2020, p.25

[95] Idem.

[96] Idem.

[97] Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence, AMI, p. 86.

[98] Idem.

[99] Idem., p. 71.

[100] Dave Miranda (2013) The role of music in adolescent development: much more than the same old song, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 18:1, 5-22, DOI: 10.1080/02673843.2011.650182

[101] Translated by The Republic.